Software Supply Chain security issues are hitting hard the whole OSS ecosystem; not a day goes by without a security incident going into the wild, affecting unaware users and companies with software built with the modern patterns of ultra composability made of a dense number of external dependencies in multiple layers.

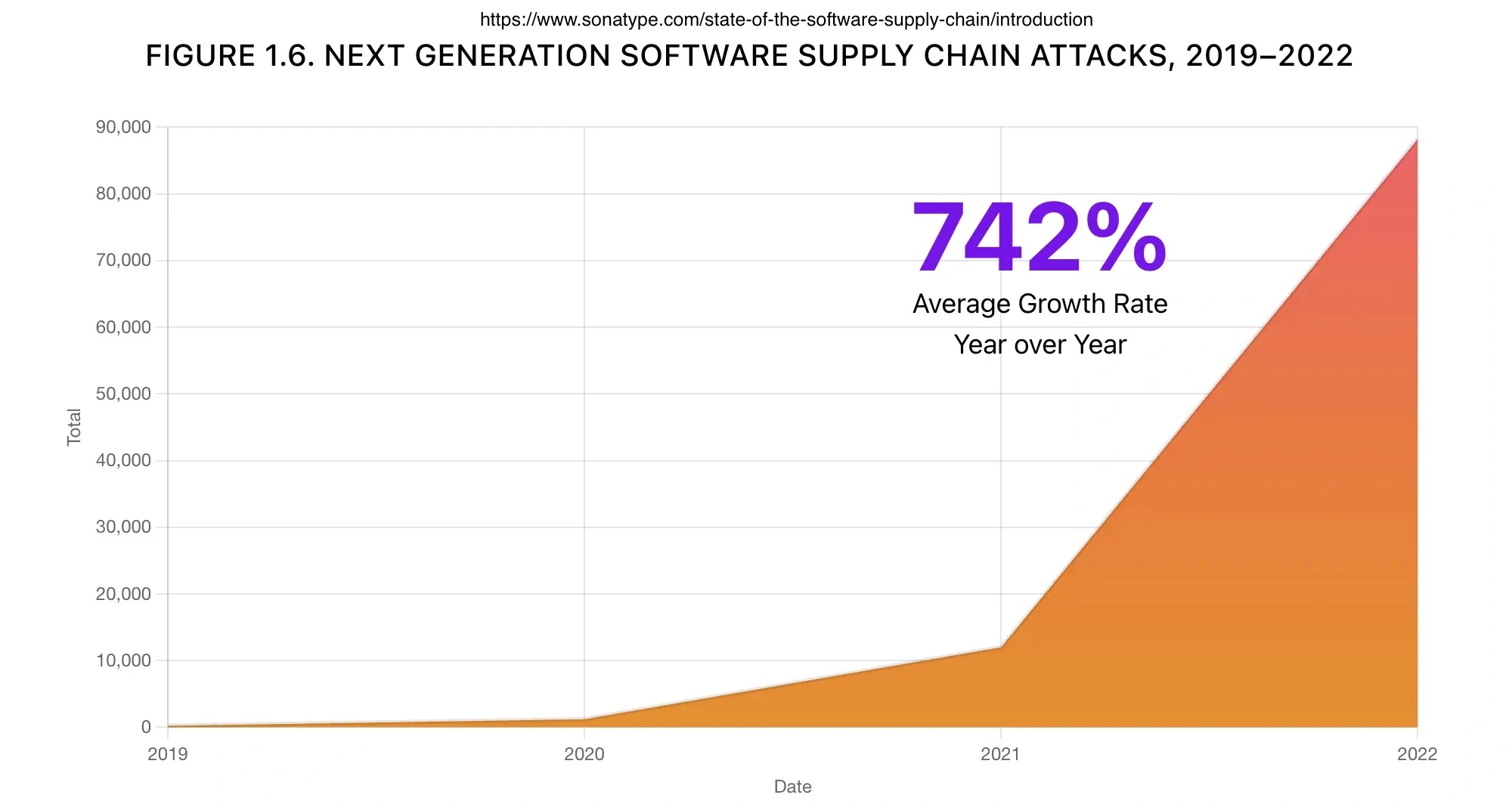

According to the research conducted by Sonatype in their annual State of Software Supply Chain, Supply Chain attacks have an average increase of 742% per year.

There are several reasons behind it, such as the higher market demand for software in all sectors and the tremendous growth of the open-source model; it is estimated that 90% of companies use open-source.

Another aspect that underpins this situation is the discovery and the evolution of cyber attacks specifically designed to attach the supply chain, like Dependency Confusion, Typosquatting and its Cousin–Brandjacking, Malicious Code Injections and Protestware.

According to the industry data, the median number of transitive (indirect) dependencies for a JavaScript project on GitHub is 683.

Dependencies remain one of the preferred mechanisms for creating and distributing malicious packages, and it is still relatively easy to forge them.

In February 2022, GitHub introduced mandatory two-factor authentication for the top 100 npm maintainers and PyPA is working to reduce dependence on setup.py, which is a key element to how these attacks can launch alongside while promoting 2FA adoption using a public dashboard (Source: https://www.sonatype.com/state-of-the-software-supply-chain/open-source-supply-demand-security)

To see the numbers in action, we will test two of the most used languages in 2022, which are Javascript and Python, and then finally a Microservices-based project made of several languages.

Javascript Link to heading

Going to bootstrap a plain Javascript NextJS codebase using the provided default settings:

| |

One thing to note is that a newly installed app already has 5 moderate severity vulnerabilities. This way of delivering messages is risky because it inadvertently teaches our brain to ignore them, whether they are useful or not. The next time a warning like this appears, it may go unnoticed. We should do better in how we present these messages.

Let’s now count the dependencies:

| |

To print a Hello World with NextJS, we need to bring 298 dependencies with 5 known vulnerabilities.

We package the application in an OCI container, as explained here in the official doc:

| |

In this case, the build produced by the NextJS is a bit smaller in terms of packages (cause using standalone mode), and Alpine base image adds just 17 packages at the moment without any known vulnerability.

This is an image ready to be shipped in production, and it counts 282 packages (NPM + Alpine) without any modification made by us; it is just the bare framework.

The large package sizes in NodeJS are primarily due to the relatively small JavaScript standard library and the Unix-inspired philosophy behind NodeJS, as explained in this blog post.

The aforementioned philosophy can sometimes lead to distortions, such as the case of packages like “left-pad” becoming part of many packages (even as a transitive dependency). This almost caused the internet to break down when the author decided to remove it due to a name dispute. You can read more about it here.

I guess this event also inspired this famous xkcd meme:

Python Link to heading

It is the second most used and the fastest growing language, with more than 22 percent year over year (source: https://github.blog/2023-03-02-why-python-keeps-growing-explained/).

To compare with Javascript, I will use Django as a test case.

| |

The situation here is better; Django has just 8 dependencies (at least the ones discovered by Syft).

As Python is the best-in-class language for AI, I wanted to try to add PyTorch as a project dependency:

| |

Even with PyTorch and its dependencies, the number of Python packages is relatively small, just 35; what is way bigger now is the number of packages carried back from the Debian base image (required to use PyTorch instead of Alpine), to be more precise 429 packages with an insane number of known vulnerabilities, even if this image is the latest stable Python 3.11 release.

Test Results Link to heading

We can see here the summarized results:

| Language | Container | Vulnerabilities (> medium) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NextJS (Javascript + Alpine) | 282 | 17 | 1 |

| Django (Python + Alpine) | 8 | 38 | 2 |

| Django + PyTorch (Python + Debian) | 35 | 429 | 152 |

It comes as no surprise that the number of JavaScript packages is much larger than that of Python. This is due to the nature of JavaScript, which has small and vertical libraries that perform one specific task.

Another interesting piece of data, which may not come as a big surprise too, is that containers based on pure Debian are large and have many known vulnerabilities, even if they are official.

CVEs vulnerabilities must be taken with care; we can see many false positives, and not everything can be exploited; that’s why Chainguard and key players in the industry have created OpenVex, to simplify is a database of “negative” vulnerabilities that can be distributed alongside artifacts to inform consumers about real exploitable threats.

Now that we have a general overview of the 2 most used language ecosystems let’s see the impact of those numbers when applied to a microservices-based project.

Microservices architecture and dependencies Link to heading

For this test, I will use a very nice project from GCP: Online Boutique is a cloud-first microservices demo application that is primarily intended to demonstrate the use of technologies like Kubernetes, GKE, Istio, Stackdriver, and gRPC and it is composed of 11 microservices in 5 different languages: Go, Node.js, Python, Java, C#

- Another important assumption to do here is that this project due to its nature is more optimized on the cloud parts than on the development aspects, such as dependencies

| |

Let’s strip the vulnerabilities lower than high and format the data in a table:

| Microservice | Language | Packages | ≥ High vulnerabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| emailservice | Python | 152 | 39 |

| checkoutservice | Go | 52 | 2 |

| recommendationservice | Python | 147 | 39 |

| frontend | Go | 71 | 8 |

| paymentservice | Node.js | 626 | 5 |

| productcatalogservice | Go | 51 | 5 |

| cartservice | C# | 25 | 0 |

| loadgenerator | Python/Locust | 137 | 33 |

| currencyservice | Node.js | 649 | 5 |

| shippingservice | Go | 37 | 3 |

| adservice | Java | 112 | 19 |

| TOTAL | 2059 | 158 |

Here we can see the entire surface of this microservices-based application, an agglomerate of programming language and operating system dependencies, for 2095 packages with 158 high and critical known vulnerabilities, huge numbers.

Node.js, again, is the most dependencies-hungry. Instead, Python has fewer dependencies but more open vulnerabilities; Java is very close to Python with the numbers.

The clear winner in this scenario is C#, just 25 libraries aggregated and 0 vulnerabilities.

Closing thoughts Link to heading

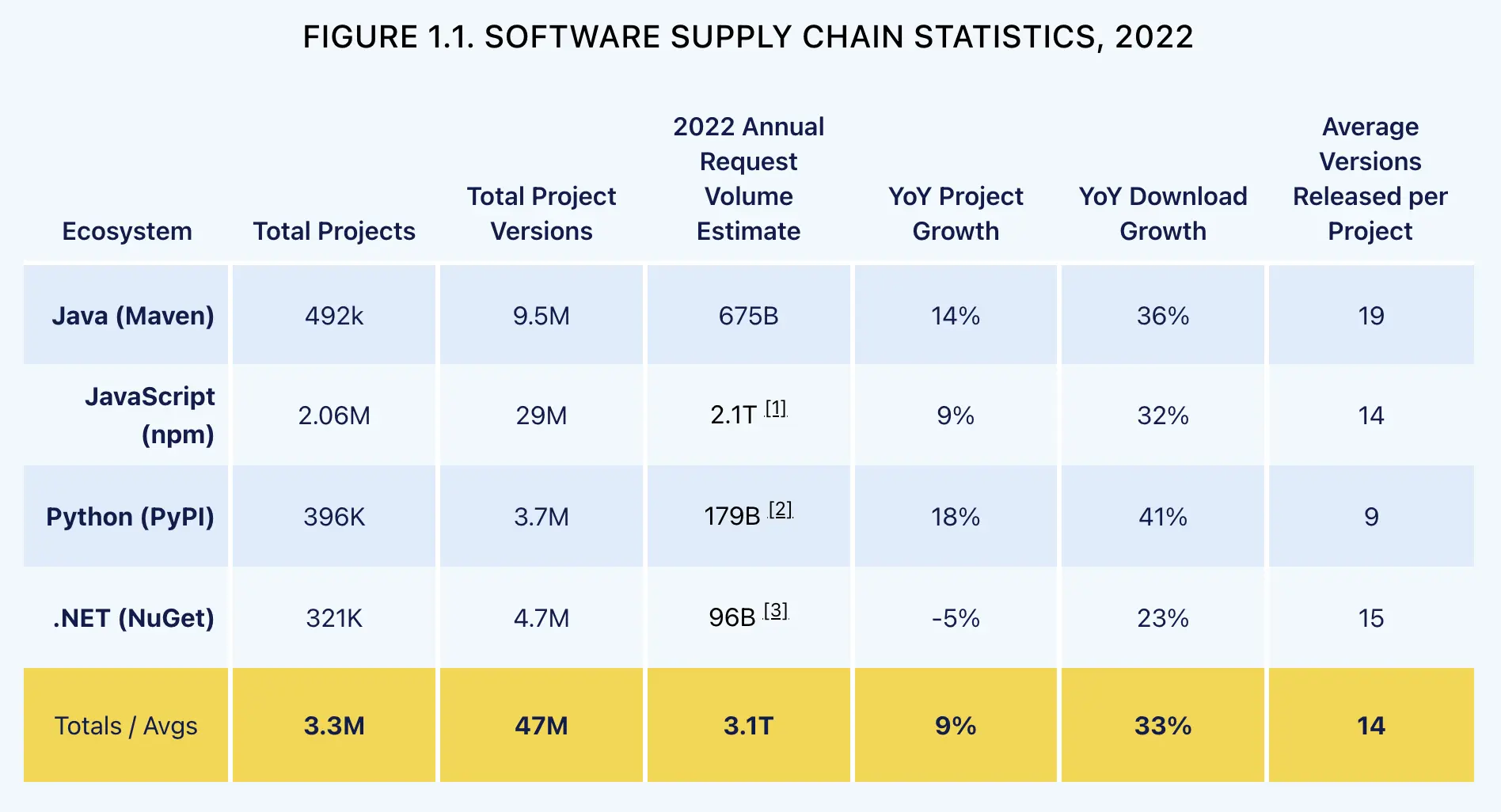

Sonatype well summarizes the non-stoppable growth of the OSS ecosystem:

https://www.sonatype.com/state-of-the-software-supply-chain/open-source-supply-demand-security

https://www.sonatype.com/state-of-the-software-supply-chain/open-source-supply-demand-security

The data show that:

- Open source development is more florid than ever; OSS won.

- The growth is spread across all the biggest ecosystems, which is very good for the entire industry; there isn’t a monopoly actor.

- An average ecosystem has 3.3M of projects, each with an average of 14 versions released yearly, which is good because the project is maintained and bad because it requires maintenance.

Today we are exposed to a high extent of complexity hidden by very powerful tools.

Grabbing a new dependency is a very low-effort task; with a modern package manager, we can assemble entire operating systems and applications composed of hundreds of thousands of external dependencies, with just one or few easy commands, and this is frankly powerful and scary

In 1984, Edsger Wybe Dijkstra in the article “On the nature of Computing Science” said that “Simplicity is a great virtue but it requires hard work to achieve it and education to appreciate it. And to make matters worse: complexity sells better”.

For my personal experience, in many years in this sector, one of the biggest enemy of this industry are the one-size-fits-all solutions that can magically solve and fix any problem, in any context, regarding the complexity of the problem, this is never the case, better to focus on the complexity of the problem.

For example, if i need to ship a static website with a bunch of HTML and CSS, i’ll never ever have the need to deploy it on a Kubernetes cluster, instead all i need is a not-so-fancy webserver.

The same apply for microservices, it’s not always the right fit even when the scenario can suggest otherwise, there are important cases like Istio or Amazon Prime Video.

And now, going back to the question of this article.

The answer is yes we are over the point of no return and and that’s not necessarily a bad thing, on the contrary i think that we are living the golden era of this industry and we have so much many opportunities as professionals or scientists like never before.

However, this also means that most projects rely on large amounts of code that may be vulnerable or malicious. This causes stress for developers and poses significant risks for the entire industry. In some cases, it can even endanger national security, as demonstrated by the Solarwinds case.

Today creating a new software product should raise some fundamental questions, such as:

- How can we trust that someone different from us can always play as a good actor?

- How can we be sure that all the code we depend on is made exclusively to do what it claims?

- How can we be sure that the software has not been tampered in one of the point of the supply chain?

In 1984, Ken Thompson, in the famous paper “Reflections on Trusting Trust” basically asked the same questions, and the moral, which I think is still valid, says that:

- “You can’t trust code that you did not totally create yourself. No amount of source-level verification or scrutiny will protect from using trusted code. To what extent should one trust a statement that a program is free of Trojan horses? Perhaps it is more important to trust the people who wrote the software.”

Even though it may have been possible to meet the developers who created and used third-party libraries in the past, it is not as feasible today due to the increased number of actors involved. Additionally, Protestware Attacks can pose a strong threat that cannot be easily countered.

Takeaways Link to heading

So, here 8 practical tasks:

- Don’t fall into the trap of using too many external libraries, think twice if you really need it, when in doubt think to left-pad disaster.

- Microservices vs Monolith is not choosing good or bad, focus on the problem instead, simpler is always better.

- Use the SLSA framework to understand modern software supply chain threats and working to adopt defined security levels, a step at a time.

- Automate dependencies management using OSS tool like RenovateBot, it’s nice and easy to integrate.

- Embrace the new era of artifact signing using Sigstore and SLSA attestations to produce your artifacts and as a guide to choosing third-party software that adopts it.

- Always produce Software Bill of Material (SBOM) for an artifact and pretend to have it too from your suppliers. (SPDX and CycloneDX standards)

- Automate and scan for known vulnerabilities across all your entire set of dependencies, it is easy to do it when standardising the artifacts to OCI containers. Using a tool like Grype.

- Use smaller Docker images like Distroless or Chainguard when possible

Thanks for reading this post. If you notice any errors or would like to discuss topics further, please get in touch with me through the usual channels. You can also join the conversation on this Github discussion thread.